The author argues that in order to create a more cohesive, compassionate, and educated society, students must be taught to use objective, reliable sources in studying multiple perspectives on an issue.

Students are often asked to argue their opinion in school, but far too seldom are they asked to find consensus with their peers. In assigning persuasive research papers, we teach students to acknowledge the opposition only to be able to negate that opposing viewpoint. The Common Core asks teachers to “Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence,” (“English Language Arts Standards”) but we limit our students when we use only the persuasive research paper to cover the Common Core’s standard of supporting a claim. While there’s nothing innately wrong with a persuasive assignment, if persuasion is all we teach, we neglect the art of reading informational texts with an open, yet evaluative mind. Instead, we encourage selective, biased reading to support personal opinion — which for teenagers is not yet fully formed. The traditional persuasive research paper contributes to the fractured society we have today. Instead, we should encourage students to see the whole picture in order to understand various perspectives on an issue.

After annually assigning a five-page persuasive research paper to my freshman English students for the past 15 years, I recently noticed a change in their approaches to writing and research. Increasingly, their arguments became filled with fallacies, their viewpoints were more extreme, and their sources included highly-biased articles, as well as websites that were not credible. Looking for an answer to these problems, I changed the assignment to include instruction on media literacy and the objective of the essay to present two main sides of an issue. In addition to requiring that varying perspectives be represented, I asked my students to search for consensus among viewpoints and to draw their own conclusions based on their research. “A well-rounded education must provide genuine learning opportunities that teach students to curate their own sources of information, find solutions to the issues they encounter in that information, and make compelling arguments for those solutions” (Olsen 94). I wanted my students to be empowered by their research to suggest a path forward for society. But to be empowered, students need to use valid sources. In turn, my instruction had to begin with research and critical reading skills.

Media Literacy: Where we get our information has changed but our teaching hasn’t caught up

To begin this journey to a new way of teaching research, I needed to help students evaluate their sources, especially those found online. A Pew Research Center survey of U.S. teens in March through April of 2018 found that 95 percent have access to smartphones, and 45 percent say they are online almost constantly. Teenagers’ social media sites of choice are YouTube (with 85 percent saying they use it), Instagram (72 percent), Snapchat (69 percent) Facebook (51 percent), and Twitter (32 percent) (Anderson and Jiang). Meanwhile, a 2017 Common Sense Media survey of children ages 10-18 showed that most don’t think they can identify fake news, and 31 percent of them had actually shared a post in the prior six months that they later found out was false (“News and America’s Kids”).

Scrolling through my own social media feeds, seeing highly-biased and deceptive posts shared by my friends, it strikes me how easy it is to confuse a biased news article with an opinion column; to conflate satire with fake news. If it all looks the same to adults, how do these articles appear to my freshman English students, many of whom have never held an actual newspaper, let alone read one? Teens are not only getting their news from social media, they are forming opinions for classwork there, too.

Holding up an actual print newspaper, I showed my class how simple it is to tell the difference in the intention of articles in print as opposed to online. Back when I was a high school freshman, I told them, it was pretty easy to identify an opinion article: A whole section of the newspaper was devoted to opinion, and it was labeled.

As my students pictured me with ‘80s hair and acid-washed jeans, I told them bias was not as much of an issue 30 years ago because newspaper reporters and television journalists were held accountable to be objective by a mainstream audience and advertisers. In 1985, the average home only received 18 channels, compared to hundreds today (Bowman). We had three major news networks that people trusted, where newscasters tried to be seen as impartial. Back when Americans watched the same network stations to get their news, we all heard the same message, as opposed to today, where a Pew Research Center study said adults who relied on network TV news fell to 26 percent in 2017 (Matsa). Shockingly, even more adults get their news from cable TV than a network — 28 percent in 2017 (Matsa)— which most likely means people are tuning in to stations that are compatible with their own biases.

Newspaper readership is falling too: “The industry’s financial fortunes and subscriber base have been in decline since the early 2000s, even as website audience traffic has grown for many” (Newspapers Fact Sheet). And a recent Pew study showed that as of August 2017, 62 percent of U.S. adults got their news from social media—mostly Facebook (Shearer and Gottfried). A side effect of what happens when we select our own news sources in our social media feeds and that we see from like-minded friends is that we only see one side of the story and our biases are not challenged. Our quest for information enforces our own bias.

Back in the days before social media, we knew where the fake news, or intentionally misleading news, would be located — in tabloids, which we might see in the checkout aisle at the grocery store, but we knew enough to be skeptical of what “enquiring minds want to know.” At the same time, satire appeared in expected places such as Saturday Night Live or in editorial cartoons; it didn’t pop up deceivingly in our news feed. Today, we should all be more critical of our information sources, but it doesn’t seem we are, especially when we agree with them.

Students cannot tell the difference between fake news, satire, biased news, and opinion

I wondered if my students would be able to identify the different types of articles in my own social media feeds, so I made a Google form survey as a pretest. Their results were incredibly poor before they received any instruction. But I was not surprised. Media literacy is often glanced over in schools, where YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook, and Twitter (the main social media outlets that teens visit) are blocked by many school servers. It’s difficult to teach media literacy when its primary texts are banned in the classroom. Students still have access to these sites on their smartphones with internet providers, but teachers might not be able to pull them up on a screen in front of the classroom to use them in lessons on media literacy. Teachers can, however, access social media sites from home and use screenshots captured from a news feed to show in a classroom.

My goal in giving a pretest to students was to identify where they found their information and how good they were at deciphering among satire, fake news, biased news, and opinion columns before I assigned an opposing sides research paper. I wanted my students to learn where to find reliable sources, and I also wanted them to realize their ignorance. My survey was a wake-up call to all of us.

One multiple choice question on the survey I gave my 22 freshmen in March 2018 was “When conducting research for a persuasive essay on a current issue, the first place I look is:” and 62.8 percent answered “the Internet/ Google.” I was hoping they would answer “Articles published on online databases such as SIRS or EBSCO,” but only 27.3 percent did. The problem with using a search engine first is that my students did not yet have the skills necessary to evaluate websites.

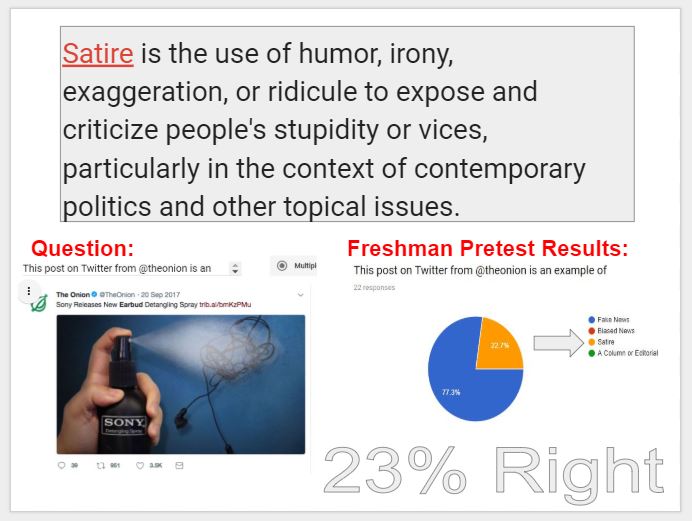

I also asked questions about social media posts. One example I gave was a satirical post from The Onion saying “Sony Releases New Earbud Detangling Spray” with a photo of a spray-bottle aimed at tangled earbuds. Funny, right? I gave four options to identify what this post was: satire, fake news, biased news, or an opinion column/ editorial. Seventy-seven percent incorrectly identified it as “fake news” while 23 percent were correct. Freshmen often don’t know the definition of satire and don’t recognize it, but after providing Oxford’s definition as “the use of humor, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to expose and criticize people’s stupidity or vices, particularly in the context of contemporary politics and other topical issues,” they did a better job with the second post I showed them, an Andy Borowitz post of a supposed news article with the headline “Trump Considering Firing Dow Jones Industrial Average.”

I also asked questions about social media posts. One example I gave was a satirical post from The Onion saying “Sony Releases New Earbud Detangling Spray” with a photo of a spray-bottle aimed at tangled earbuds. Funny, right? I gave four options to identify what this post was: satire, fake news, biased news, or an opinion column/ editorial. Seventy-seven percent incorrectly identified it as “fake news” while 23 percent were correct. Freshmen often don’t know the definition of satire and don’t recognize it, but after providing Oxford’s definition as “the use of humor, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to expose and criticize people’s stupidity or vices, particularly in the context of contemporary politics and other topical issues,” they did a better job with the second post I showed them, an Andy Borowitz post of a supposed news article with the headline “Trump Considering Firing Dow Jones Industrial Average.”

Teens are easily deceived into thinking publications that look like news articles are truthful. It’s important to teach Kylene Beers and Robert E. Probst’s new definition of nonfiction from their book Reading Nonfiction: Notice & Note Stances, Signposts, and Strategies: “Nonfiction is that body of work to which the author purports to tell us about the real world, a real experience, a real person, an idea or belief” (21). Beers and Probst remind us that not everything that looks or acts like it’s nonfiction is true, so we must not teach high school students that fiction means “false” and nonfiction means “true.”

Teens are easily deceived into thinking publications that look like news articles are truthful. It’s important to teach Kylene Beers and Robert E. Probst’s new definition of nonfiction from their book Reading Nonfiction: Notice & Note Stances, Signposts, and Strategies: “Nonfiction is that body of work to which the author purports to tell us about the real world, a real experience, a real person, an idea or belief” (21). Beers and Probst remind us that not everything that looks or acts like it’s nonfiction is true, so we must not teach high school students that fiction means “false” and nonfiction means “true.”

In the next survey question, I showed a well-circulated example of fake news in the form of two juxtaposed photos of gun-control advocate Emma Gonzalez, a student from Parkland: the real one of her ripping a target next to an altered photo of her ripping apart the Constitution (Relman). My question: ”Someone digitally altered a video of a student from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, claiming she ripped apart the Constitution when she was really ripping apart a target. That was an example of: Fake News, Biased News, Satire, or Opinion Column/ Editorial.” I was glad to see that half of my students were able to say this was fake news. But even with the description, 36 percent thought it was satire. I wonder how many would think it was something other than fake news without my detailed description of what was going on and the two photos placed next to each other. I showed the Collins Dictionary definition of fake news: “false, often sensationalized information disseminated under the guise of news reporting.” I made sure to point out that the intent behind the post was important in deciding whether this was fake news or satire. Was it made to be funny by cleverly pointing out an issue in society? No. Was it created to deceive people into being angry about something? Yes. That’s fake news.

We also looked at another post that purported to be a photo of a wall built by Mexico to keep out Guatemalans. It said “Mexico Guadamala Border Built by Mexico to keep them out!!! Funny how it is okay for Mexico but racist for Trump to build a wall.” (Memes in Your Email). We talked about ways to figure out that this post was fake: the misspelling of “Guatemala” showed it was not trustworthy and the highly inflammatory language was meant to make others feel bad. We talked about fact-checking sites that are easy to use to verify stories, such as Snopes.com, FactCheck.org, PolitiFact.com. The American Press Institute and the Washington Post both have fact-checking categories on their websites, too. In addition, it’s fun to look at the Snopes “Hot 50” with students to see what the latest fact checks on the site are and to check stories students see in their own news feeds.

Other lessons on fake news included watching an excellent one-minute video from CommonsenseMedia.Org explaining its concept called “5 Ways to Spot Fake News.” We studied the CRAAP test from the Meriam Library which shows criteria for evaluating information: Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose. This is a great test that I will consider requiring students to submit in writing in the future.

Moving on to teaching bias in the media, I posted an excerpt from an article from the Daily News titled “President Trump Reportedly Doesn’t Read Top-secret Intel Briefs, Breaking with Decades of Presidential Practice” stating:

But an administration insider with knowledge of the situation told the Washington Post that Trump doesn’t read the daily intel memo because it’s not his preferred “style of learning.” Instead, the source said, Trump has opted for oral briefings, augmented with photos, videos and colorful graphics.

The revelation that Trump doesn’t read the classified brief underscores his well-documented short attention span and unusual approach to the presidency (Sommerfeldt).

While a whopping 46 percent of my students incorrectly identified the above article as “a column or editorial,” the good thing is they could detect the bias in this piece that was published as straight news. Twenty-seven percent correctly categorized the article as “biased news.” They pointed out the descriptor of “colorful graphics” making it seem more elementary. They also saw the editorialized comment at the end that the revelation “underscores” Trump’s short attention span.

Bias is complex. We spent more time studying this category than others. We looked at the headlines on Allsides.com, which has clickable newspaper headlines of the big issue of the day: one from the left, one from the right, and one from the center. It’s a great tool to see how each ideology handles not only the headlines of an issue, but also what each includes in an article on the same topic and how it is written. Allsides.com also has an clear chart ranking how conservative or liberal news outlets are, and it compares this to a separate community feedback chart of the same media outlets. Charts help me as a teacher to show students why they will lose some of their audience by quoting news sources that are seen as untrustworthy because they are perceived to be excessively biased. Another excellent chart that ranks the trust levels of media outlets by conservatives and liberals is found on Businessinsider.com, and it is based on a study conducted by the Pew Research Center ending in April 2014. Finally, a detailed chart from the website www.adfontesmedia.com tells where media outlets fall on a horizontal axis from liberal to conservative, and then on the vertical axis it shows from the least reliable to most reliable at the top. Printed or downloadable high-quality copies of the chart are available for purchase, and permission to share it online is granted, and copyright permission to use in the classroom will be granted by the author Vanessa Otero upon request.

Studentnewsdaily.com offers tools to teach what bias is. My favorite part of this site is a list of types of bias with explanations of each, which the site has excerpted and adapted from How to Identify Liberal Media Bias by Brent H. Baker. These types of bias include: bias by omission, bias by selection of sources, bias by story selection, bias by placement, bias by labeling, and bias by spin. The site also defines the terms “liberal” and “conservative” for students.

Finally, we talked about columns and editorials. None of my students were able to identify the example I shared with them in my Google form as a column. They had never been taught about opinion columns before. After reading columns of Ann Coulter and Leonard Pitts, opinion writing was much easier for them to identify. I let students know that reading columns for research isn’t wrong, but readers must be aware of what the author’s purpose is (going back to the CRAAP test), and for a column, the purpose is more than to simply inform, but to persuade. Columnists are incredibly important to democracy: they are the watchdogs for our elected officials, they are informed enough to help us put together the whole picture, and they can help us make good choices. But for a research paper, it might be a good idea to read columns to understand how each side feels about an issue in order to find the main arguing points, then to look for sources that are more neutral in bias to cite in the paper.

One more thing I want students to take note of before doing research online is that when we visit library databases of journal articles, the school pays a subscription for us to have that research service. When we visit free websites via a Google search, we may not have to pay for them, but we aren’t really getting them for free. Julie Smith says in her book Master the Media, “The fact to remember is that, if you aren’t paying to use a website, then you are the product being sold” (107). Smith goes on to explain that advertisers can target and reach consumers through cookies, messages that web servers pass to your web browser which are saved there, reaching back out to the server when you request another page, enabling advertisers to send ads that appeal directly to you. “The Internet exists to deliver people to advertisers, not to deliver content to people” (Smith 107).

Assignment Procedure for Opposing Sides Research Paper:

After spending a week teaching about fake news, satire, biased news, and opinion columns; finding credible sources with the CRAAP test; avoiding plagiarism; structuring an outline; and writing in MLA style, we start writing. We begin by picking topics from a list I provide of social issues. I allow other topics upon my approval. I give about two weeks for the research, drafting, peer editing, and revision of the paper. One important step in the process is verbally discussing the topic with peers (and me) to collect and structure ideas.

The Assignment:

The assignment is to write an opposing sides paper where the student examines a controversial issue in order to help a reader better understand the two main sides of the debate on this topic. The goal is not to argue a specific position on the topic, but rather to explain the most compelling points on two sides of the topic and support those points using a variety of credible outside sources.

Requirements:

- Four to six pages in length typed, double-spaced in 11-point Arial font.

- Write a well-defined, well-written introduction paragraph — It will include a hook, which captures the reader’s’ attention, an explanation of why the issue is important, background info describing the current situation of the issue today, and a thesis statement that lays out some of the overarching main points of the topic. (i.e. A critical debate has developed between those individuals who support keeping backyard chickens and those who oppose allowing farm animals in city limits.)

- The body of the essay will present the main arguments for each position. The simplest construction may be to fully present one side and then the other, trying to be fair in the number of sources and the length of each argument. Consider beginning the presentation of each side with a “because” statement, outlining the 2-4 main reasons you will address from that side. (ie: People who are in favor of keeping backyard chickens within city limits cite the greater nutritional value of the eggs, the more humane treatment of the birds, and the educational value for the families who keep them.) Try to find a statistic, expert opinion, anecdote, or other citable evidence to back up these main points of your paper because you are being evaluated on your ability to use research to support ideas. Finally, transition to the other side of the issue and repeat the same technique.Other organization ideas are also acceptable

- The essay will end with the conclusions you made based on your research; therefore, you should write the conclusion in first person. Try to find the places where both sides can reasonably agree (ie: Based on my research, I found that both sides of the backyard chicken issue care about the safety of people and chickens, so few would argue that chickens belong in small backyards close to other neighbors. I believe a reasonable solution to the issue is to…)

- At least six in-text citations, correctly formatted for MLA style.

- Works cited page written on a separate page, correctly formatted, showing at least six reliable sources. Three of the sources you use in your paper must be from a journal or newspaper article such as what we find using EBSCO and SIRS. Only one source may be an encyclopedia. You may also use reliable websites and books. (You may not use Wikipedia, but if you see something you want to use on Wikipedia, search for that information in other sources, possibly found in the Wikipedia citations.)

Findings:

I was happy with the results of this assignment. My students seemed to learn more from their research, and we didn’t have any awkward conversations about why a source was not acceptable. I had fewer students using extreme techniques for arguing, and while I don’t recall ever having a student accuse me of giving a poor grade based on my own biases of an issue, I think that this assignment further safeguards against fielding an accusation like that. One thing I want to explore in the future is encouraging writing the entire paper in first person, mostly from the influence of reading Thomas Newkirk. If students personally comment on their research, they will be more engaged and evaluative, explaining why they chose the main points and evidence they used as well as what they chose to leave out. “By assuming a tone of assured factuality and certainty, the writing disguises its own bias….But facts must be located and chosen, and these very acts introduce a bias” (Newkirk 63-4). It would be engaging to read an essay where students wrote phrases such as “One piece of research that surprised me was…” or “a false narrative I saw repeatedly shared about this issue was…” More importantly, it would be engaging for them to write that way.

Another possibility for improvement is requiring students to fill out evaluation forms using the CRAAP test for their sources. In the post-writing Google survey I gave to students in May, with 20 students participating, they self-reported that their research had improved. I asked “In writing your research paper, where is the first place you looked for information about your topic?” Results showed 90 percent of my students said “Articles published on online databases such as SIRS or EBSCO” (up from 63 percent in the pre-assessment survey.)

In a follow-up question, I asked “Where did you find most of your information for your opposing sides research paper?” Seventy-five percent responded “Articles published on online databases such as SIRS or EBSCO,” while 25 percent said “The Internet/ Google to search for web articles.” My own observations of students’ works cited pages confirmed their self-assessment. But I am more concerned about their ability to evaluate sources than where they look for information.

I gave my freshman class a survey to find out what they needed to know and to help assess if they learned it. My survey won’t show other teachers what their students know, but might give others ideas of what to ask students in their own classrooms. I hope to diminish the flow if misinformation online through teaching my students media literacy.

JoAnn Gage serves on the executive board of the Iowa Council of Teachers of English, is a Master Journalism Educator in the Journalism Education Association, and has taught at Mount Vernon Community Schools since 1996.

Works Cited

“5 Ways to Spot Fake News.” Common Sense Media: Ratings, Reviews, and Advice, Common Sense Media, www.commonsensemedia.org/videos/5-ways-to-spot-fake-news.

“50 Hottest Urban Legends.” Snopes.com, www.snopes.com/50-hottest-urban-legends/.

Anderson, Monica, and Jingjing Jiang. “Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018.” Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech, 31 May 2018, www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/.

“Balanced News via Media Bias Ratings for an Unbiased News Perspective.” AllSides, 28 Feb. 2018, www.allsides.com/unbiased-balanced-news.

Barthel, Michael. “Newspapers Fact Sheet.” Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project, 13 June 2018, www.journalism.org/fact-sheet/newspapers/.

Beers, G. Kylene, and Robert E. Probst. Reading Nonfiction: Notice & Note Stances, Signposts, and Strategies. Heinemann, 2016.

Borowitz, Andy. “Trump Considering Firing Dow Jones Industrial Average.” The New Yorker, The New Yorker, 6 Feb. 2018, www.newyorker.com/humor/borowitz-report/trump-considering-firing-dow-jones-industrial-average.

Bowman, Karlyn. “The Decline Of The Major Networks.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 19 June 2013, www.forbes.com/2009/07/25/media-network-news-audience-opinions-columnists-walter-cronkite.html#463ddea847a5.

“The Chart, Version 3.0: What, Exactly, Are We Reading?” All Generalizations Are False, www.allgeneralizationsarefalse.com/the-chart-version-3-0-what-exactly-are-we-reading/.

Engel, Pamela. “Here Are The Most- And Least-Trusted News Outlets In America.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 21 Oct. 2014, www.businessinsider.com/here-are-the-most-and-least-trusted-news-outlets-in-america-2014-10.

“English Language Arts Standards » Writing » Grade 9-10.” Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2018, www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/W/9-10/.

“Evaluating Information-Applying the CRAAP Test.” Miriam Library, California State University, Chico. http://www.csuchico.edu/lins/handouts/eval_websites.pdf

“Fake News Definition and Meaning” Collins English Dictionary, www.collinsdictionary.com/us/dictionary/english/fake-news.

“Information Sources Pre-Writing Survey” Google Form. 5 Apr. 2018.

“Information Sources Post-Writing Survey” Google Form. 8 May 2018.

Matsa, Katerina Eva. “Fewer Americans Rely on TV News; What Type They Watch Varies by Who They Are.” Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, 5 Jan. 2018, www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/01/05/fewer-americans-rely-on-tv-news-what-type-they-watch-varies-by-who-they-are/.

“Media Bias.” Student News Daily, www.studentnewsdaily.com/types-of-media-bias/.

“Media Bias Chart Version 3.1.” All Generalizations Are False, www.allgeneralizationsarefalse.com/shop/.

“Mexico Wall Mexico Guadamala Border Built by Mexico to Keep Them Out Funny How It Is Okay for Mexico but Racist for Trump to Build a Wall.” Me.me, me.me/i/mexico-wall-mexico-guadamala-border-built-by-mexico-to-keep-13059662.

Newkirk, Thomas. Minds Made for Stories: How We Really Read and Write Informational and Persuasive Texts. Heinemann, 2014.

“News and America’s Kids: How Young People Perceive and Are Impacted by the News” Common Sense Media. January 2017,

https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/news-and-americas-kids

Olsen, Casey. “Teaching Informed Argument for Solution-Oriented Citizenship.” English Journal, vol. 107 no 1, 2018, pp. 93-99.

Otero, Vanessa JD. “Media Bias Chart 4.0: What’s New.” Ad Fontes Media, Aug. 2018, www.adfontesmedia.com/.

Relman, Eliza. “A Doctored Photo Showing a Prominent Parkland Shooting Survivor Ripping up the Constitution Went Viral on Right-Wing Social Media.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 26 Mar. 2018, www.businessinsider.com/parkland-student-emma-gonzalez-ripping-up-constitution-doctored-photo-2018-3.

“Satire | Definition of Satire in English by Oxford Dictionaries.” Oxford Dictionaries | English, Oxford Dictionaries, en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/satire.

Shearer, Elisa, and Jeffrey Gottfried. “News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2017.” Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project, 7 Sept. 2017, www.journalism.org/2017/09/07/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2017/.

Sommerfeldt, Chris “Trump Reportedly Doesn’t Read Top-Secret Intel Briefs.” NY Daily News, NEW YORK DAILY NEWS, 9 Feb. 2018, http://www.nydailynews.com/news/politics/trump-reportedly-doesn-read-top-secret-intel-briefs-article-1.3810822

“Sony Releases New Earbud Detangling Spray.” The Onion, Www.theonion.com, 18 Oct. 2017, www.theonion.com/sony-releases-new-earbud-detangling-spray-1819592988.